Kindergarten in Arizona teaches students how to spell simple words, count by fives, and many other useful skills. In dozens of neighborhood public schools throughout Arizona, students now have the option of learning a second language through dual-language immersion programs.

Mandarin Choice dual-language immersion program at Coronado Elementary School in Gilbert teaches kindergarteners and first graders Mandarin in an engaging and interesting way.

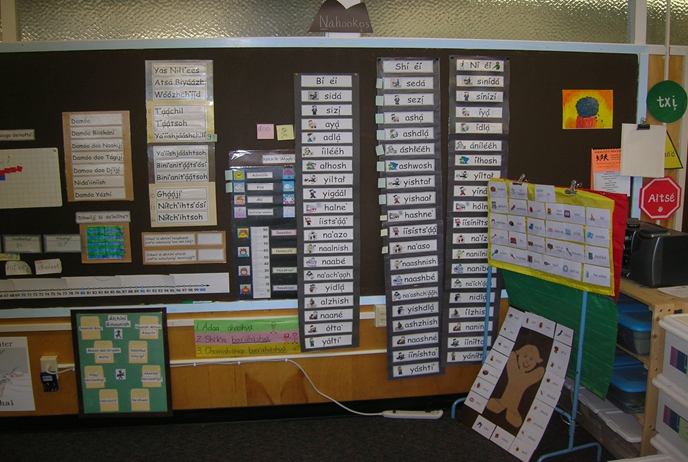

In Hozho Bridge’s classroom, students learn Navajo. The photo is courtesy of the Hozho School Bridge

In Flagstaff, students attend Puente de Hózhó School from kindergarten to fifth grade and are immersed in either Navajo (Diné) or Spanish language and culture.

“Our kids and parents understand that it gives them an edge,” said Dawn Trubakoff, principal of the bilingual magnet school in Flagstaff Unified School District. The idea of kids speaking two, three, or four languages is nothing to them in other countries. It’s not something we take for granted in America.”

Currently, Scott and Bonny Dolinsek’s son is enrolled in the dual-language Spanish/English program at Kyrene de los Ninos School.

Parents appreciate the program because it gives their children a gift that will only benefit them and last a lifetime,” Bonny said. “Bilingualism will provide him with more job opportunities, cultural experiences, and overall life opportunities. The fact that our son will receive a Kyrene education while learning a second language makes us so happy! ”

In the past three years, there have been nearly 1,000 dual-language immersion programs across the country. More than 40 dual-language programs are available in Arizona’s public schools, and the number is growing.

According to Natalie Luna Rose, communications specialist for Vail School District in Tucson, the Confucius Institute at the University of Arizona has approached the district about starting a Mandarin/English dual language immersion program for kindergarteners at Mesquite Elementary School this fall.

In a Hozho Bridge classroom, students work on Navajo lessons. The photo is courtesy of the Hozho School Bridge

Because adults don’t remember what it was like to be that age, we underestimate what they are capable of,” Rose said. “If we give them the chance, they can achieve amazing things.”

Earlier this year, Vail observed kindergarten students at a Cave Creek Unified school participating in a Spanish immersion program.

Rose said that the minds of these children were ready to absorb and adapt so quickly. Even though a few students struggled to understand the teacher’s Spanish, they were able to figure out what was going on, and there was no stress. The students were eager to learn and excited to get started.”

To replicate in every way possible the language acquisition and proficiency acquired in a home and family environment as acquired in a school setting, the Tuuba City Unified School District in Coconino County is redesigning its Diné language immersion program for grades K-12. According to Adair Klopfenstein, Native American studies director for the district, the program is being redesigned.

Dr. Harold Begay, Superintendent of Tuuba City Unified, is dedicated to seeing Navajo and Hopi languages and cultures flourish long into the future through district programs to “Embrace and incorporate community cultural values and wisdom, use indigenous languages and cultural knowledge to enable and promote harmonious concordant personal, social, and educational growth, and engage and stimulate minds with traditional native cultural knowledge and wisdom”, Klopfenstein said.

According to Trubakoff, second languages teach persistence and a different way of solving problems.

Parents visit and take part in classroom activities at Puente de Hozho School. Photo courtesy Puente de Hozho School

It also expands the number of people they can communicate with, since students can use English and Spanish to talk to people in 187 countries, said Luis Melo, fifth grade Spanish teacher at Puente de Hózhó.

“The world’s no longer small,” Rose said.

Learning a second language helps students develop creative and critical thinking, and helps the U.S. remain competitive in the global market, Rose said.

Coronado teachers understand the world is becoming increasingly global, and that schools need to prepare students today for the technologically advanced and internationally connected economy of the future, Wong said.

“Knowing a second language will help prepare our students to be successful leaders in a global society,” Wong said. “Mandarin is the most useful language to conduct business in, second only to English. If you speak Mandarin and English, you can speak to 50 percent of the world’s population. That is a powerful tool to have at one’s disposal.”

Dual-language programs also are a “net pulling together families,” Melo said.

“Our kids learning Navajo are able to go back to the reservation and understand their siblings and grandparents living there who use Navajo only, by using the language they are learning here,” Melo said. “We have some teachers who do not know any Spanish, and they use their kids who go here to translate and interpret.”

A word wall in a Navajo language classroom at Puente de Hozho School in Flagstaff. Photo courtesy of Puente de Hozho School

Tuba City Unified’s Navajo and Hopi language instructors appeal to students on many levels in order to engage them, encourage them and sustain students’ communication in their native language, Klopfenstein said.

“We want this communication to spill over to the homes in the hogans,” Klopfenstein said. “Our parents and grandparents are overjoyed to hear their kids and grandkids expressing themselves in their native language and using language to communicate basic needs.”

Puente de Hózhó provides an environment where different cultures are valued and there is a strong sense of community, Trubakoff said.

“We enrich and learn from each other,” Melo said.

Parents and students don’t have to be embarrassed if they don’t speak English well, because “we’re all about teaching non-English speakers how to speak English and non-Spanish speakers how to speak Spanish,” Trubakoff said.

Some Navajo parents have told Trubakoff they are grateful their children are learning Navajo in school, because many of the parents do not speak Navajo themselves.

“We don’t try to fix any kids. If they don’t speak any English, we’re not fixing them, they’re not broken,” Trubakoff said. “They have this wonderful gift that half the class wants from them. They have a gift to give us.”

Last year, Coronado Elementary with support from College Board and Arizona State University’s Confucius Institute offered an after-school Chinese Culture club, added Chinese culture to social studies classes and began Mandarin Chinese language instruction for kindergartners, Wong said.

“They love singing the songs, counting and learning to write the language,” Wong said. “Even young children understand the power of speaking another language.”

The Higley Unified School District plans to expand the program each year to offer a pre-kindergarten to high school early language option and currently offers Mandarin in middle and high school, Wong said.

“Our parents appreciate the opportunity to have their children participate in a program that previously was reserved for only the elite private schools or international schools,” Wong said. “They are thrilled that their children have the potential to reach mastery of a foreign language that they can actually use at the professional level in the future.”

Kyrene School District will expand its dual-language program from Kyrene de los Ninos in Tempe to Kyrene de los Lagos in south Ahwatukee and “the principal and one of the teachers who started it all are going to lead the effort at Lagos,” said Jeremy Calles, chief financial officer for the district.

Calles said the dual=language program has made a real difference at Kyrene de los Ninos.

“Ninos was built to hold over 700 students, but only had 400 and out of our 25 schools it was the lowest performing school with a C,” Calles said. “Now it is a B school and well on it’s way to earning an A, it should be there within the next couple of years. Also it’s packed, the program has a waiting list and the spots fill up as soon as we open up Open Enrollment in January. The school will start the year with over 700 students. Increased enrollment and achievement, we couldn’t ask for anything more.”

The dual-language program has brought families to Kyrene from all over the valley and there is still space available in Kindergarten at Kyrene de los Lagos in Ahwatukee, said Dolinsek, community relations specialist for the district.

“There is also a program available for early learners, Bienvenidos, offered at two sites, Lagos and Norte,” Dolinsek said. “This program is to prepare the children for the Dual Language classroom during the elementary years.”

For more info on this program and the dual language, please call 480-541-1000.

Flagstaff parents are so interested in Puente de Hózhó’s program there is a long waiting list. In Vail’s program, the kindergarten class is full, but there might be some room in first grade and an open house for parents will be held July 10. The Mandarin Choice program at Coronado Elementary is still taking applications for the fall.

In Flagstaff, parents and community members said they wanted children to learn Navajo and Spanish languages and culture, so the district’s director of bilingual education applied for and was awarded a Title VII grant for indigenous languages which funded the (Navajo) Diné/English and Spanish/English programs, Trubakoff said.

“The program started out with kindergarteners, the next year we added first graders, then the next year second graders and we rolled it on up all the way through fifth grade,” Trubakoff said.

In Puente de Hózhó School’s Diné/English program, 25 kindergartners and 25 first graders are immersed in Navajo language and culture, Trubakoff said. In second and third grade they spend half their time learning math and science in Navajo and half their time learning language arts and social studies in English. Then in fourth and fifth grade the students are mixed in with the students in the Spanish/English program.

In Tuba City Unified, students are immersed in Diné and Hopi that is aligned with the traditional learning model and the Dine Philosophy of Learning, use technology for digital storytelling and in their flipped learning classrooms, and take part in project/experiential learning, Klopfenstein said.

Flipped learning lessons introduce each week’s lessons and objectives, help reteach concepts, and also provide enrichment, Klopfenstein said. There is a minimum of one required flipped lesson per week required by each instructor.

“This engagement of students in the language activities before they reach the classroom allows our instructors to facilitate instruction rather than revert back to traditional lecture style,” Klopfenstein said.

Experiential/project-based learning gives teachers an opportunity to incorporate cultural teachings, crafts and skills into the curriculum such as weaving, moccasin making, basket making, traditional dancing, arts and crafts, ethnobotany and food preparation activities, Klopfenstein said.

In Puente de Hózhó School’s Spanish/English program, it’s a 50-50 dual-language program in which students learn math and science content in Spanish from a native Spanish-speaking teacher and language arts and social studies content in English from a native English-speaking teacher, Trubakoff said. All content is aligned with Arizona’s College and Career Ready Standards.

Vail and Higley’s Mandarin programs content instruction follows a similar format.

“It’s amazing how quickly they switch from one language to another, including the pronunciation and intonation,” Melo said. “They don’t even think about it, but they do it automatically when they switch from one language to another.”

Puente de Hózhó students also write essays in Spanish and English, and do science projects in Spanish and in Diné.

“The dual language immersion model is the most effective and efficient way to teach a language,” Wong said. “It is the same natural and easy way that humans learn a language at a young age. Our kindergarteners learned it so quickly, they just think it is a game.”

Research indicates that “young children learning in two languages show increased brain activity when using the target language,” and that “bilingual brains are physically heavier than monolingual brains,” Wong said.

Dual-language immersion students master Mandarin at a far higher level than students who start learning a foreign language in high school, Wong said.

“Learning a second language at an early age, especially one as difficult as Mandarin Chinese will protect the child’s ability to sound like a native speaker,” Wong said.

Even if less time is spent learning mathematics in the target language, dual-language students show the same or better achievement when compared with students who only speak one language, Wong noted.

Puente de Hózhó students’ AIMS scores are just as high or higher than those of the district, county and state, Trubakoff said.

“We have a very high English Language Learner population, obviously a high Hispanic population and a high Native American population and we’re pretty high poverty as well, but our kids (AIMS) scores are great,” Trubakoff said. “That means they’re working hard and are able to connect it.”