Underfunding of federally mandated special education services for public school students, coupled with a growing number of students with more severe disabilities, is straining general classroom spending in Arizona’s public schools.

The state’s formula funding for special education is now $79 million less than what district and charter schools spend to provide the services required under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, according to a recent analysis by Dr. Anabel Aportela, director of research for Arizona Association of School Business Officials and Arizona School Boards Association.

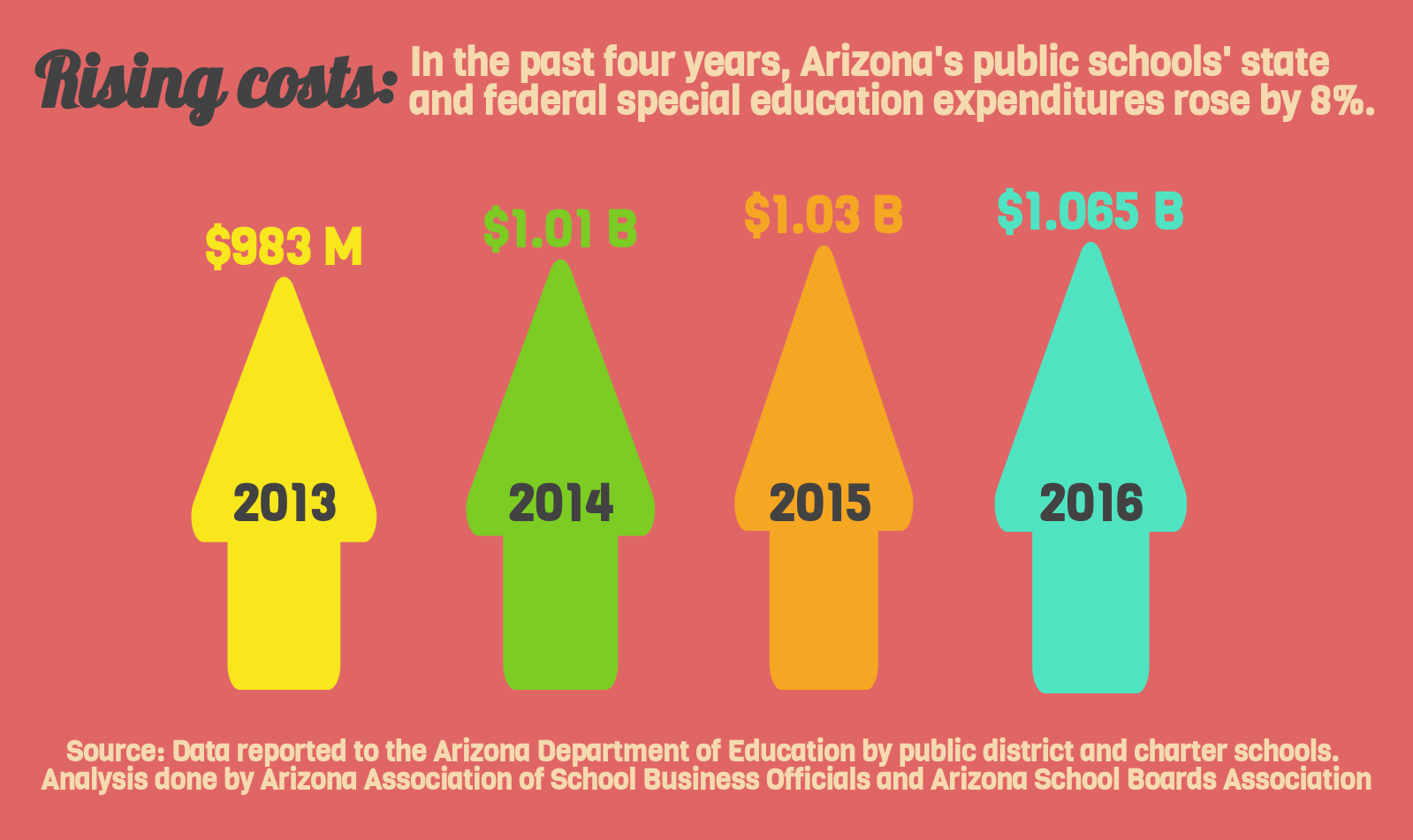

Statewide, special education expenditures exceed $1 billion and have increased 8 percent since 2013, Aportela said.

Infographics by Lisa Irish/AZEdNews

Click here for a larger version

Aportela’s analysis examined state maintenance and operations revenues and expenditures, the special education teacher portion of Classroom Site Fund expenditures and Federal IDEA revenues and expenditures, but excluded expenditures paid through other federal funds such as Impact Aid and special education transportation costs, which can be significant.

Not adequately funding special education forces districts to make cuts to general education programs, said Dr. Chuck Essigs, a former special education teacher who is director of governmental relations for Arizona Association of School Business Officials.

“Districts have no choice but to fund special education programs since they are mandated by state and federal law; therefore, the only place that districts can make cuts are in non-special education programs,” Essigs said.

That impacts classroom spending, because you have to come up with money that isn’t there to pay for therapists, or bus aides or school bus service for special education students, Aportela said.

“Where is that money going to come from? Your general operations, so you’re going to increase class sizes, you hire fewer teachers and you don’t have raises for teachers,” Aportela said.

The dollars in the classroom debate

Public education advocates contend that the underfunding of special education impacts all public school students and also creates public misconceptions about how schools are using their resources.

When the Arizona Auditor General’s report claimed classroom spending in Arizona decreased this year, its narrow focus did not take into account support services and legally-mandated special education that are key to students’ learning.

The auditor’s report, released March 1, focuses on spending on instruction as the barometer of support for Arizona students. A broader definition the governor, Legislature and Arizona public school leaders agreed upon in the 2015 budget includes instruction, instructional support and student support services.

That broader definition includes reading and math intervention specialists, media specialists, librarians, counselors, social workers, nurses, psychologists and speech, occupational and physical therapists in that total.

Why and how are costs rising?

Another critical factor is the increase in state and local special education expenditures for services, which rose 32 percent from 2007 to 2015 for Arizona district and charter schools, according to data provided to the Arizona Department of Education.

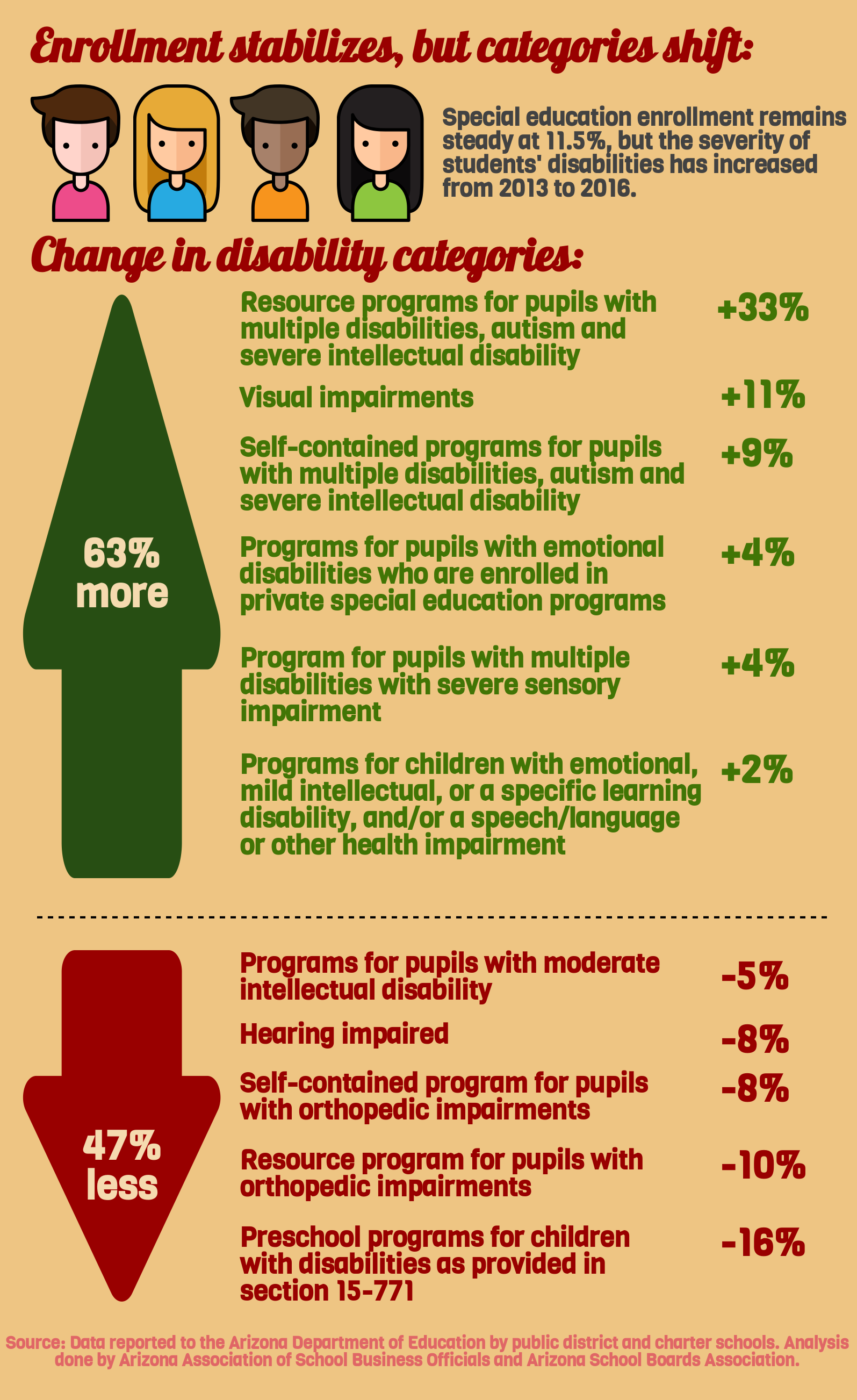

While the number of Arizona district and charter school students enrolled in special education has remained flat at 11.5 percent since 2013, a change in the types of students’ disabilities may account for this increase in costs, Aportela said.

Over the past four years, the number of students with mild disabilities has decreased slightly from 9.78 percent to 9.64 percent, while the number of students with more severe disabilities has increased from 1.75 percent to 1.86 percent, with the largest increases in students with autism and visual impairments Aportela said.

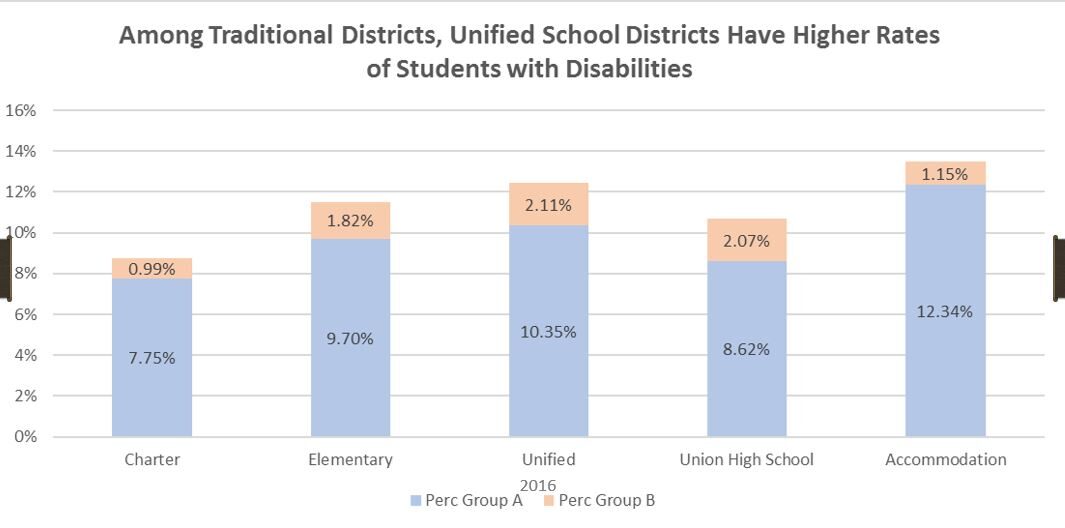

Funding to serve students with disabilities categorized as Group A is calculated by the state on a per-pupil basis. That means that if a school enrolls 100 students, then each of those 100 students is generating a per-pupil amount that is intended to cover the costs for these types of disabilities. Disabilities included in Group A are specific learning, emotional, mild intellectual, speech language impairment, developmental delay and other health impairments.

Funding for students with disabilities in the Group B category is calculated on an identified student basis. If there are five students at the school with those disabilities, the school will receive funding for those five students. Disabilities in Group B include orthopedic impairment, preschool students with disabilities, moderate intellectual, visual impairment, hearing impairment, autism, severe intellectual, multiple disabilities and severe sensory impairments.

More additional funding is provided for students in Group B than in Group A.

“Over the years, it’s been about 85 percent of the students are Group A and only about 15 percent of the students have been Group B,” Essigs said.

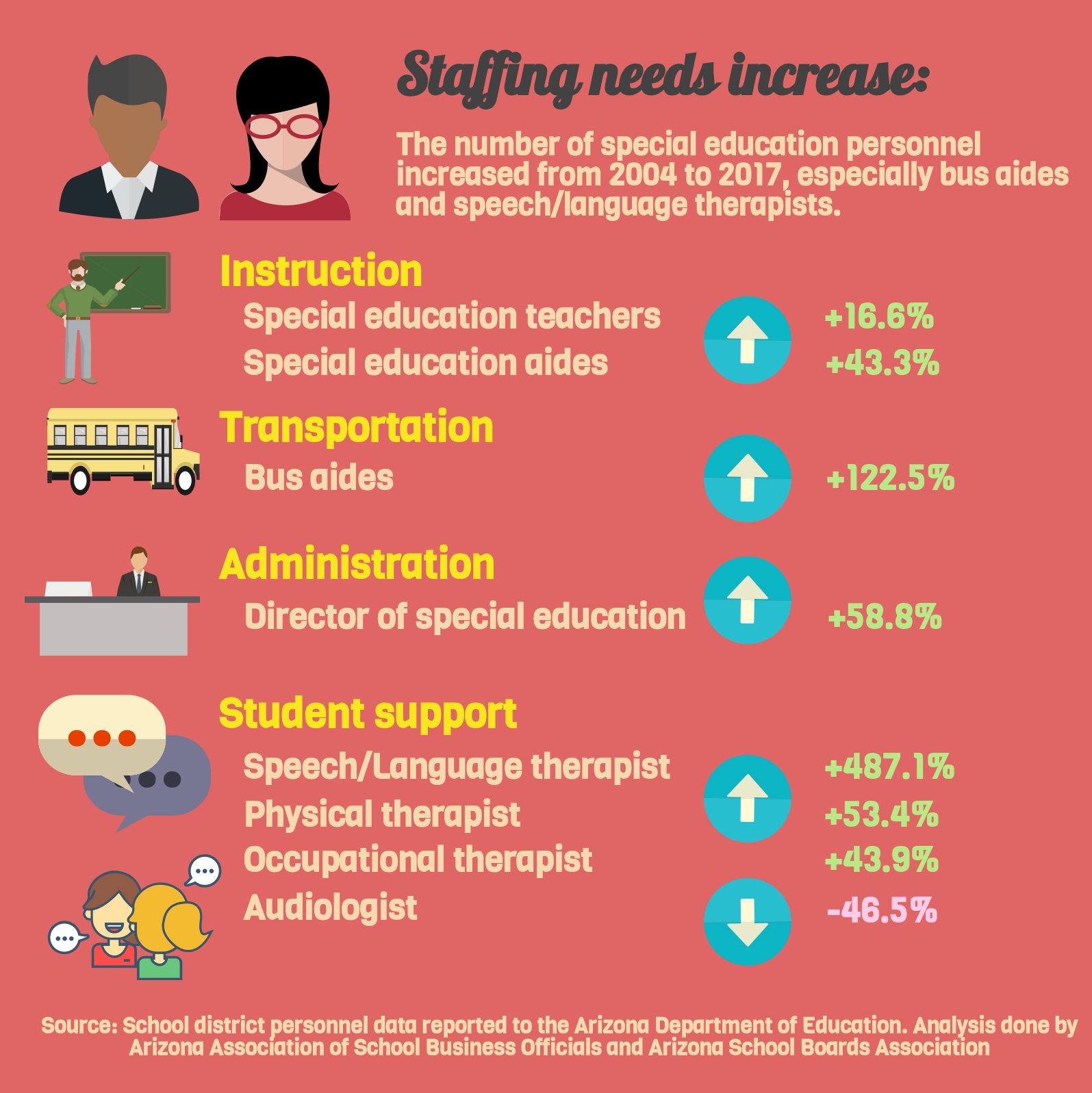

The increase in the severity of students’ disabilities has been one factor in the 16.6 percent increase in district special education teachers from 2004 to 2017, and the 43.3 percent increase in special education aides, Aportela said.

During that time, a 122.5 percent increase in bus aides and a 104.4 percent increase in special education support services, which include occupational, physical and speech/language therapists and audiologists has also led to increased special education expenditures, Aportela said.

Properly supporting special education students extends to transportation as well. Bus aides are often mandated in special education students’ Individualized Education Plans as necessary for door-to-door service as are health and other monitoring. These are considered transportation expenditures, not special education or classroom instruction expenditures.

“Most districts that I talk to are still facing the problem that the special education transportation costs far exceed what the transportation funding gives them to spend,” Essigs said.

How much more is needed?

While the recent analysis tells part of the story, education advocates say more is needed to inform the discussion and estimate what it will take to close the special education funding gap.

For that reason, education advocates say the push is on for an updated special education cost study to show what it would take to fully fund special education.

The last study, done in 2007, found that schools didn’t receive enough money to cover services required by law, forcing them to take money from other areas including services, programs or opportunities for students who don’t need special education. At that time, the deficit was $318 million.

Last legislative session, Sen. Sylvia Allen sponsored Senate Bill 1037, which would have required the Arizona Auditor General to conduct a special audit and cost study of school district and charter school special education programs. The bill passed in the Senate on a 30-0 vote on Feb. 28, 2017, and it passed in the House Appropriations Committee on an 11-3 vote on March 15, 2017, but the bill was later held in the House.

That’s not stopping public education groups, said Chris Kotterman, director of governmental relations for Arizona School Boards Association.

“School districts take their obligation to serve special education students very seriously, and will continue to provide the resources necessary to meet their needs,” Kotterman said.

“However, special education is costly, and the Legislature must recognize that by shortchanging the special education formula, they are hindering districts’ ability to accomplish our shared goal; namely, a top-notch public-school experience for every student, regardless of ability, location, or socioeconomic status,” Kotterman said.

“Every decision has consequences, and inaction is itself a decision,” Kotterman said.